Blue Collar Blues

@words.in.my.veins

@poorarzhangy

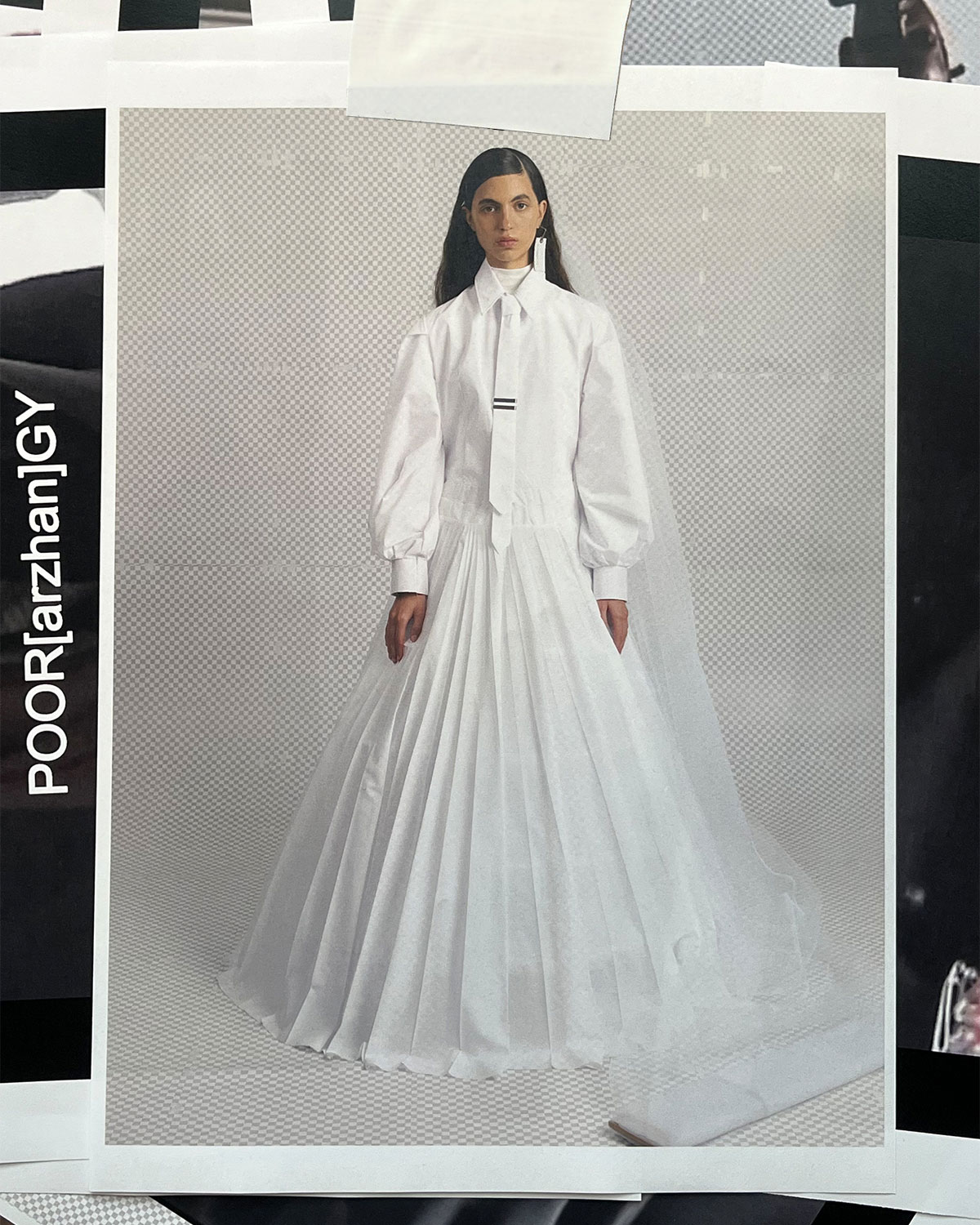

How Amin Eilzadeh’s POOR[arzhan]GY Embraces Working-Class Roots And Challenges The Status Quo.

“Our (grand)parents wore blue, so we can wear white.” It is one of Amin Eilzadeh’s favorite sayings, one that captures the essence of his family’s working-class background which the Iranian designer honors with his new brand Poorarzhangy. Named after his mother, the brand is a reflection of heritage, structure and tension, playfully and intelligently poising the line between conflict and connection. Poorarzhangy’s key colors are inspired by the American labor system where collar colors used to define purpose and class. So-called blue-collar workers are known to perform manual labor or skilled trades such as manufacturing, carpentry or construction while white-collar workers typically perform administrative or managerial tasks in an office setting. Historically, blue-collar workers have been looked down upon or disregarded, even though they are the ones who essentially keep society running.

Poorarzhangy is asking us to re-evaluate our judgement and challenge a system that aims to keep us divided through class, race, borders, and so much more.

Before the term “blue-collar” was first used in a newspaper in Iowa in 1924 the “bleu de travail” (work blues) had already originated in France with the Industrial Revolution. The period brought a need for specific work clothes that would protect their wearer, provide comfort and were cheap to manufacture. In 1844 Adolphe Lafont is believed to have made the first standardized Bleu de Travail – an unlined blue cotton moleskin jacket with a rounded shirt collar and different pockets for tools and personal belongings. What’s interesting is that until the 1700’s blue dyed fabric had been reserved for nobility and royalty since the color was extracted from indigo, lapis lazuli or woad and therefore expensive to use. Around 1704 the Berlin laboratory Diesbach and Dippel accidentally discovered a synthetic blue dye that is now known as Prussian blue and became the dominant color for professional clothing such as military or navy uniforms. In the meantime, managers or supervisors would wear white or black, and around the 1960’s workers started abandoning their blue-collar uniforms because they were becoming aware of the class stigma the color carried.

This changed again with the 1968 student revolts in Paris where young, middle-class students would wear blue to show their unity with the working class. Over the course of not much more than a month, French society was upended, with more than 10 million workers on strike, factories and universities occupied. Police were unable to beat back and even had to conceal their badges to avoid being heckled in working-class neighborhoods. Workers were gaining experience in struggle and militancy, coming to identify themselves as revolutionaries through the experience of May ‘68. It is a beautiful testament to the possibility of revolutionary struggle, enriching the legacy of the blue-collar.

Lower Saxony Dreams tells Eilzadeh’s story of growing up in the city of Hannover with a dream to explore the world of fashion, starting with very few resources and opportunities. Raised by his mother while his father was waiting for his asylum application, Eilzadeh started developing an interest in fashion at the age of fourteen. During his final year of high school in 2020 he started hand-stitching letters onto pants and later bought a small children’s sewing machine for 20 Euros that his mother showed him how to use. “She has always stood by my side through every stage of my life and believed in me – even when I told her I wanted to drop out of school to focus solely on fashion” Elizadeh recounts fondly. From the brand’s original name Sold Out Brains, to RFUGEE in 2024, having its rebrand honor his mother feels true to Eilzadeh. “I wanted to look beyond myself and not have my personal story at the center of my work anymore.”

From the name to the logo, Poorarzhangy’s identity is fluid. Eilzadeh had spent years looking for a logo but was never really able to assign anything to himself. Once invented to prevent counterfeiting, logos are now primarily used for aesthetics and to create exclusive communities that are (financially) inaccessible to most. While this idea has been rejected by some fashion houses like Maison Margiela in 1989, some brands like Jaquemus have made their name their logo. “I don’t want to own a logo”, Elizadeh confesses.

In January 2024, Eilzadeh went to a EuroShop to get some tapes. What he found was a pack of four colors – the colors he had built his brand around. “I just wanted to cover a spot with the tape, so I stuck it on the clothes – and somehow was really convinced by the look. I could decide the color, shape, and placement very quickly and change it at any time, which I liked a lot.” The tapes represent a DIY mentality and allow people to customize their looks, which in turn gives Elizadeh new ideas for future designs. “You can stick the tape on any random shirt or object, and it will carry the accent of Poorarzhangy”, Elizadeh explains.

On the question of ownership and accessibility it’s hard not to think of brands like Carhartt, Wranglers, Timberland or Dickies who have their root audience in working-class communities and different subcultures. Making their way from sole workwear to the wardrobes of hip hop legends like Tupcac, the queer community who celebrated its androgynous look, as well as skater and Chicano culture in the 2000’s - workwear brands were known to be accessible and inclusive. But with the rise of social media these styles have broken out into the mainstream, leading for example to Carhartt’s Work in Progress collection which sells more than $300 dollar cargo pants to celebrities such as Gigi Hadid or Jonah Hill. Brands like Celine, Vetements or Stella McCartney have also jumped onto the trend, sending uniforms and boiler suits down their runways.

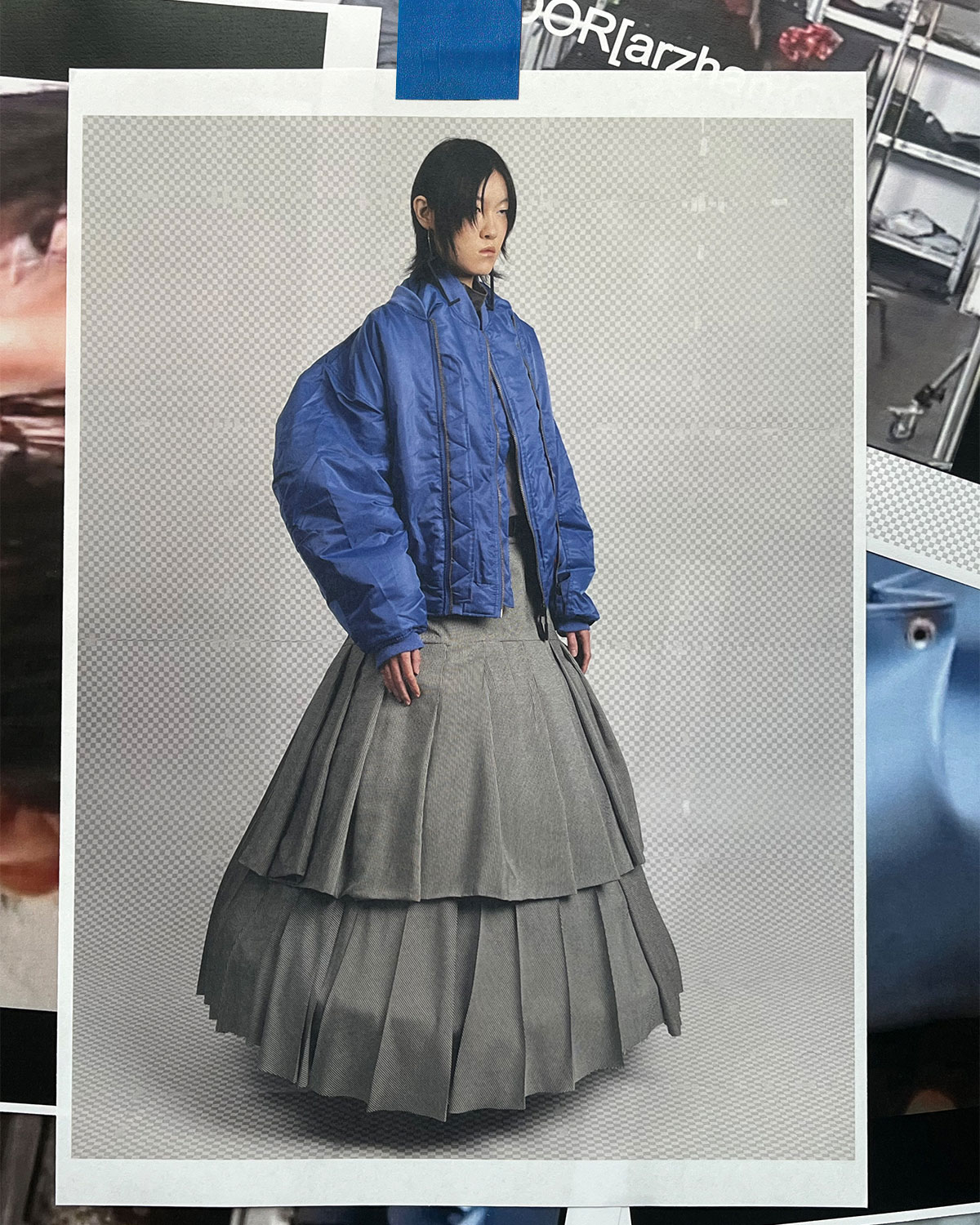

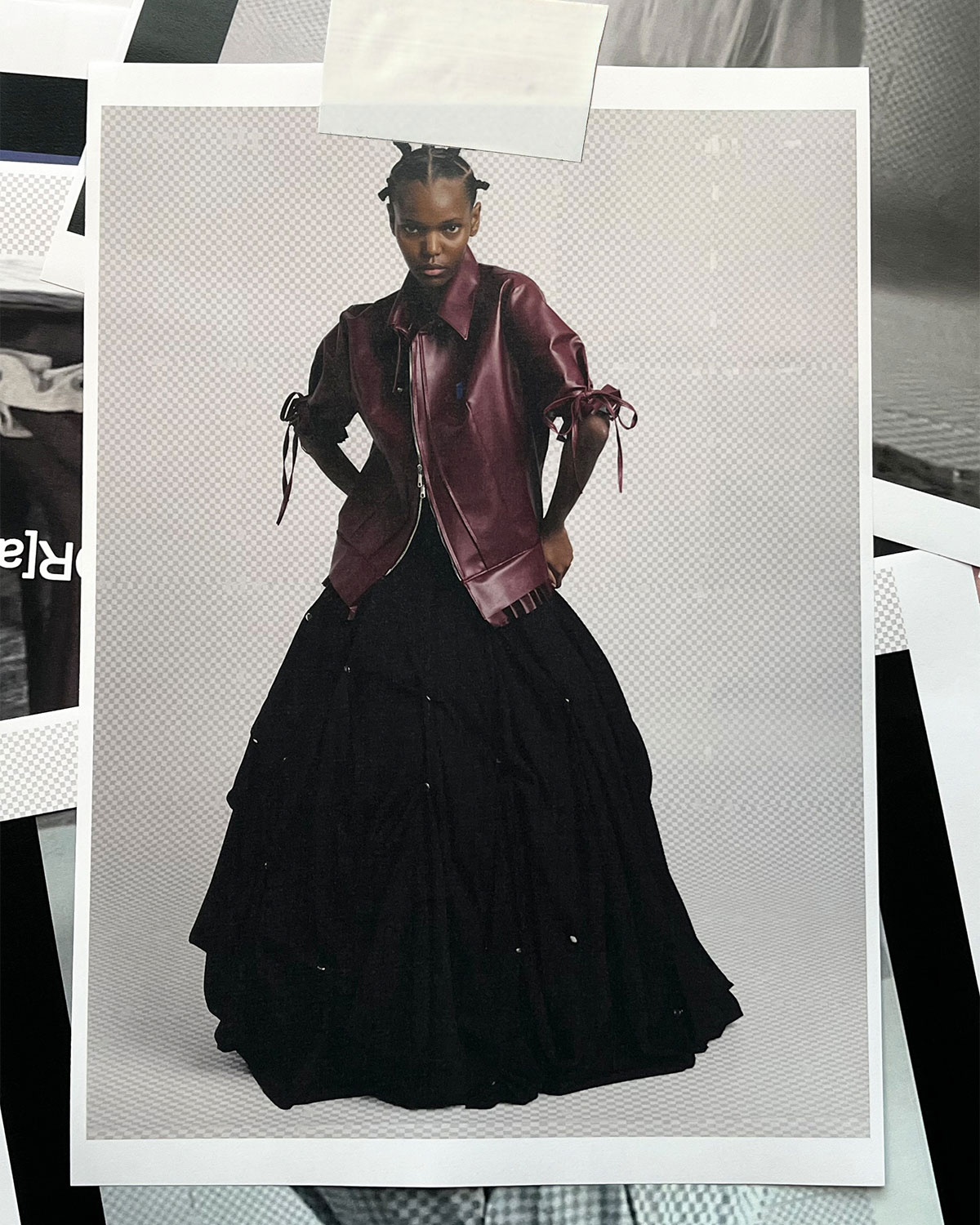

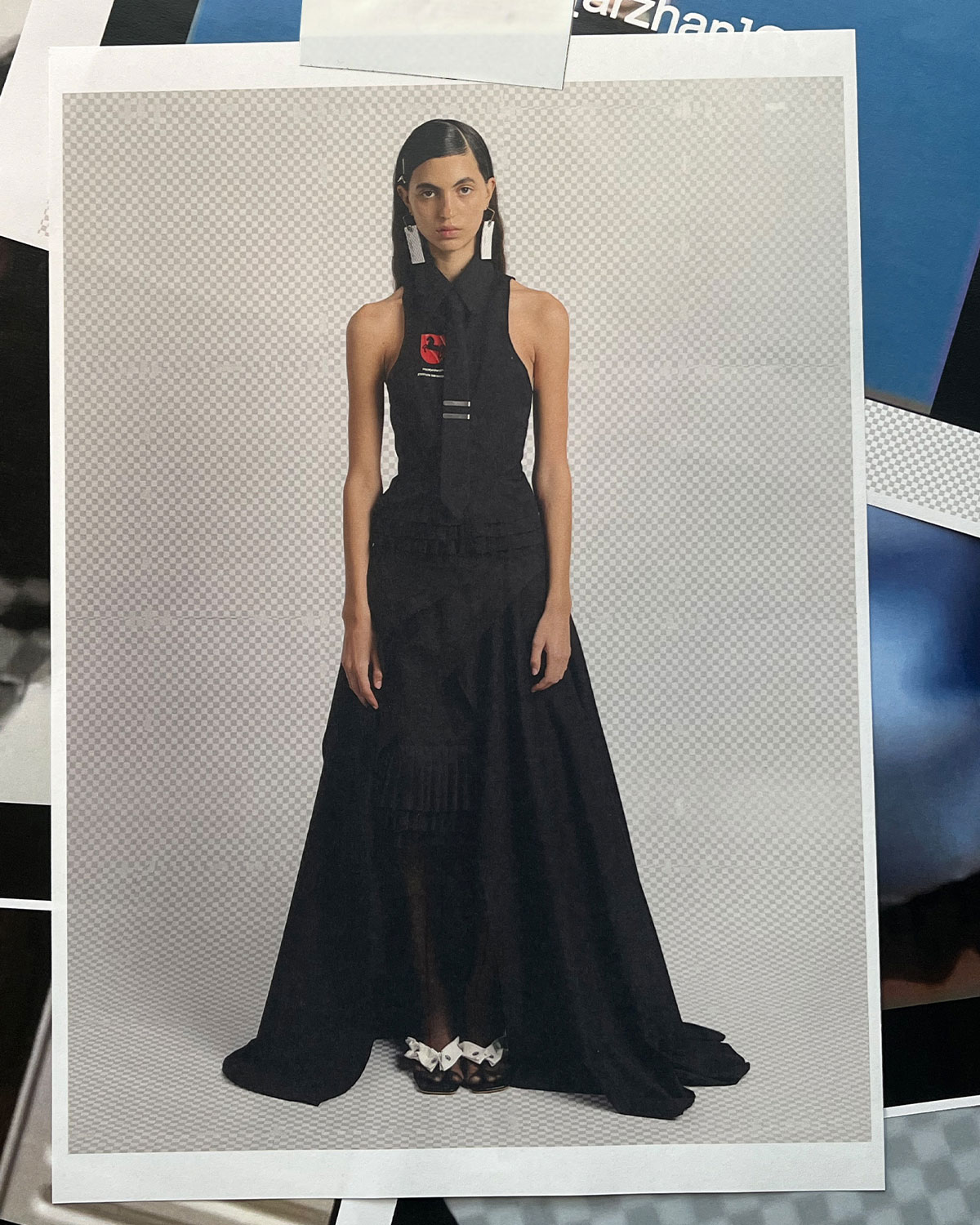

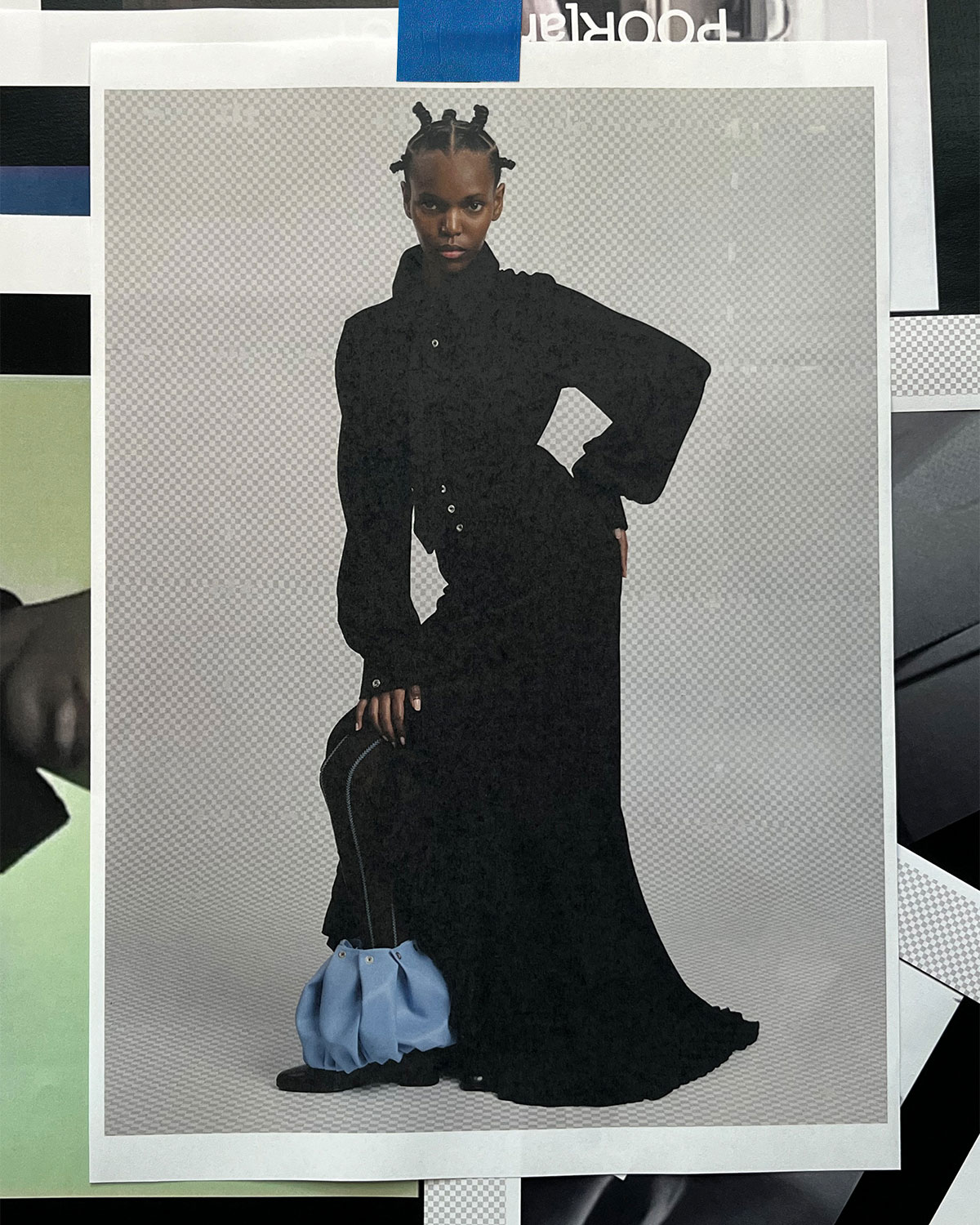

LSD [lower-saxony dreams] WOMENS SS//26

CREATIVE DIRECTOR @amin.eilzadeh

CREATIVE DIRECTION @rvminski @olarebiszz

SHOT BY @olarebiszz

EIDT @amin.eilzadeh

LIGHT @fabivn

WORN BY @meyron_ [via] @majin_mgmt / @ruilin_d [via] @majin_mgmt / @katawllnwbr [via] @izaio.modelmanagement

STYLING @amin.eilzadeh

STYLING ASSISTANCE @bour_m_

NAILS @nailsistar

HAIR @bella_kpedu

MAKE UP @mimiberk

SET DESIGN @mimiberk

SET CONCEPT @mimiberkBTS @di.santorino @fabivn

In a think-piece on Input called Funny and unreal: How blue-collar workers feel about workwear as fashion by Maya Ernest, they interview Phil and Mona Courtman who work in roofing and landscaping, having worn Carhartt pants for more than twenty years. “Our workwear gets really damaged”, Ms. Courtman explains. “It wouldn’t make sense to spend hundreds on work clothes if they have to be replaced every six months.” Her husband adds: “We’re the real work in progress.” It appears that workwear brands are slowly alienating the audience that made them big in the first place, while high fashion brands appropriate the aesthetic because it resonates with consumers.

On the other hand, we’re craving the stability and comfort we connect with the past, which is why nostalgia seems to have such a stronghold on pop culture and the fashion industry alike. Poorarzhangy has a unique grasp of the pulse of time, managing to merge the two aesthetics in a way that leaves room for interpretation, growth and anything the future might bring.

Eilzadeh is part of a new generation of designers who are unafraid to challenge the status quo and who have the drive and passion to keep reinventing our idea of what fashion is and can be. “My goal is to have a fashion house, to design for one, and to organize runway shows”, he tells Majin. “I believe that if you go wide, you can conquer more. Since I’m still very young, I can afford to experiment a lot and don’t want to limit myself to just one thing. I’m very privileged to even have the choice to do fashion – and with the resources, time, and information I already have, there’s so much that can be achieved.”